don’t be fooled

There are some benefits to having started working in the used and rare book field back in 1982. Training, for one. I worked for people like Rick Wilkinson who had many years of experience and I learned from them. Expectations, for another. We all expected each other to be knowledgable about the deep intricacies of our trade.

Here’s where I started learning the book trade.

That’s one reason I attended the Colorado Antiquarian Book School not once, but twice. It’s a great way to really learn how to be a book dealer.

Back in the day, the very first thing any bookseller was taught was the definition of “first edition,” and why such an object was of value.

The idea is that the first edition is, hopefully, the closest thing to the author’s intentions. Also, it’s the most crucial historic moment in the life of that book. This is why collectors prize first editions.

The problem is in the definition of the term. Book dealers and collectors have one definition, while publishers have a different definition. And a large number of today’s online booksellers are completely ignorant of that difference.

To be absolutely perfectly clear: for collectors and dealers, the only object properly called a “first edition” is the very first release of that book. There is no such thing, to us, as a “first edition, third impression” or “third printing.” We would call that a third edition of the title.

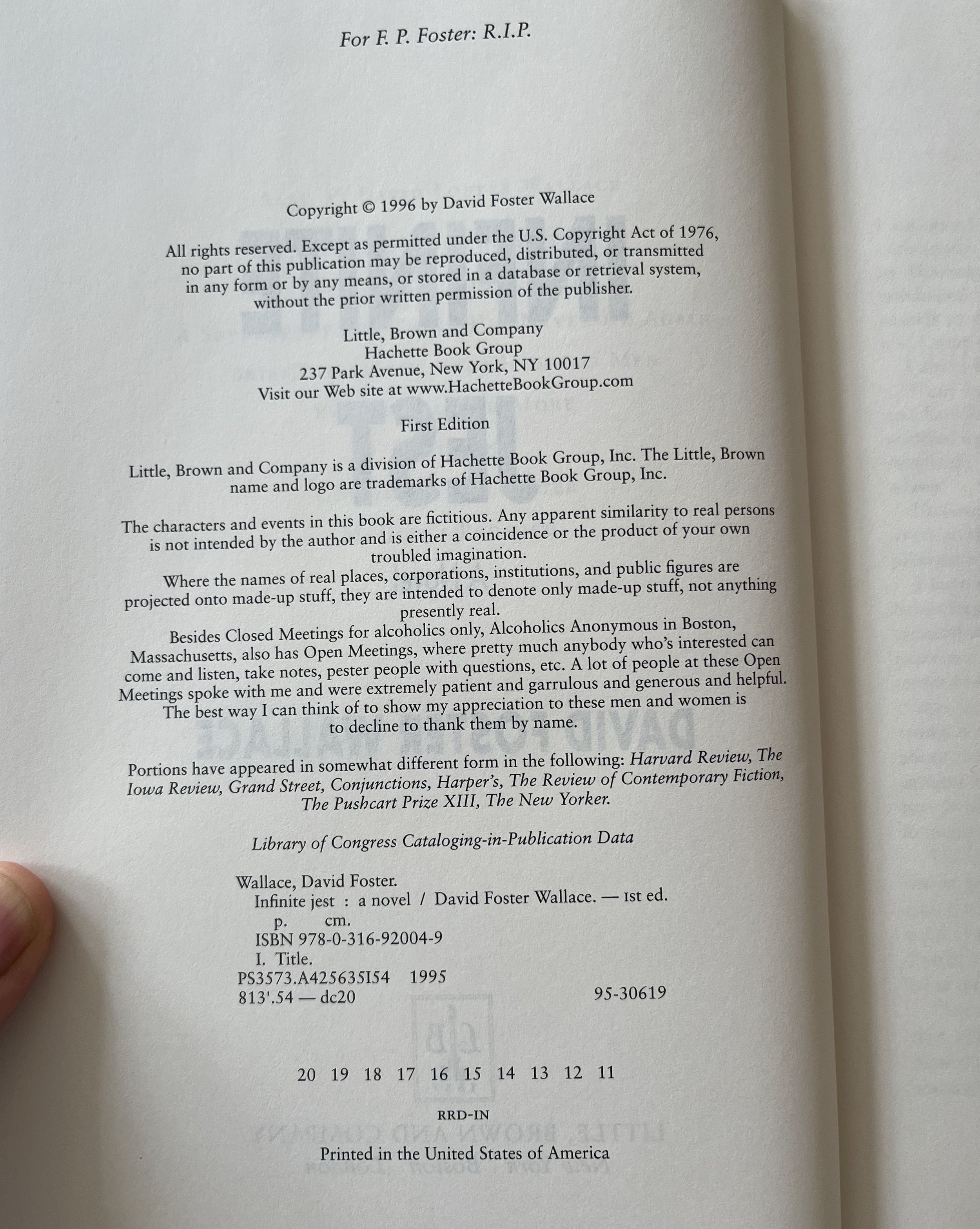

My wife’s copy of Infinite Jest says “First Edition” on the copyright page, but it is actually the 11th edition. (See the string of numbers at the bottom?) She had no idea it wasn’t a real first. Happily, she bought it to read, not as a collector’s item.

Book publishers, on the other hand, define a first edition as that text which has not been significantly revised or altered between printings. Hence they will label a book “first edition” even if it’s a later “impression” or “printing.” These days, most publishers use a string of numbers on the copyright page which indicate the book’s actual edition. (But this can vary—see my book recommendation below.)

This is further complicated by the fact that different publishers have used different ways of indicating a true first edition over the years. (See my recommended book below for sorting this out.) Also, sometimes in the middle of the printing of a first edition, a change is made to the book or the dust jacket. That is considered a second state or second impression of the first edition, as long as both states were released to the public at the same time.

Why is this all such a big deal? Because a reputable book dealer currently lists a copy of the first edition of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest for $1,000. This book dealer includes enough detail for me to believe, together with their reputation, that it is the true first.

Whereas another online bookseller lists a “first edition, second printing” of the same title for $295. The problem is, to a collector or dealer of modern first editions, it isn’t a first edition at all. It’s a second edition and not of much interest, if any.

Now imagine you bought the “first edition, second printing” for $295 thinking it was a great deal on an actual first edition. How do you think you’d feel when you got the news that it wasn’t worth much?

Unfortunately, such practices have forced booksellers who know better to qualify their descriptions by saying “first edition, first printing.” All of which only encourages the ill-informed to continue their practices.

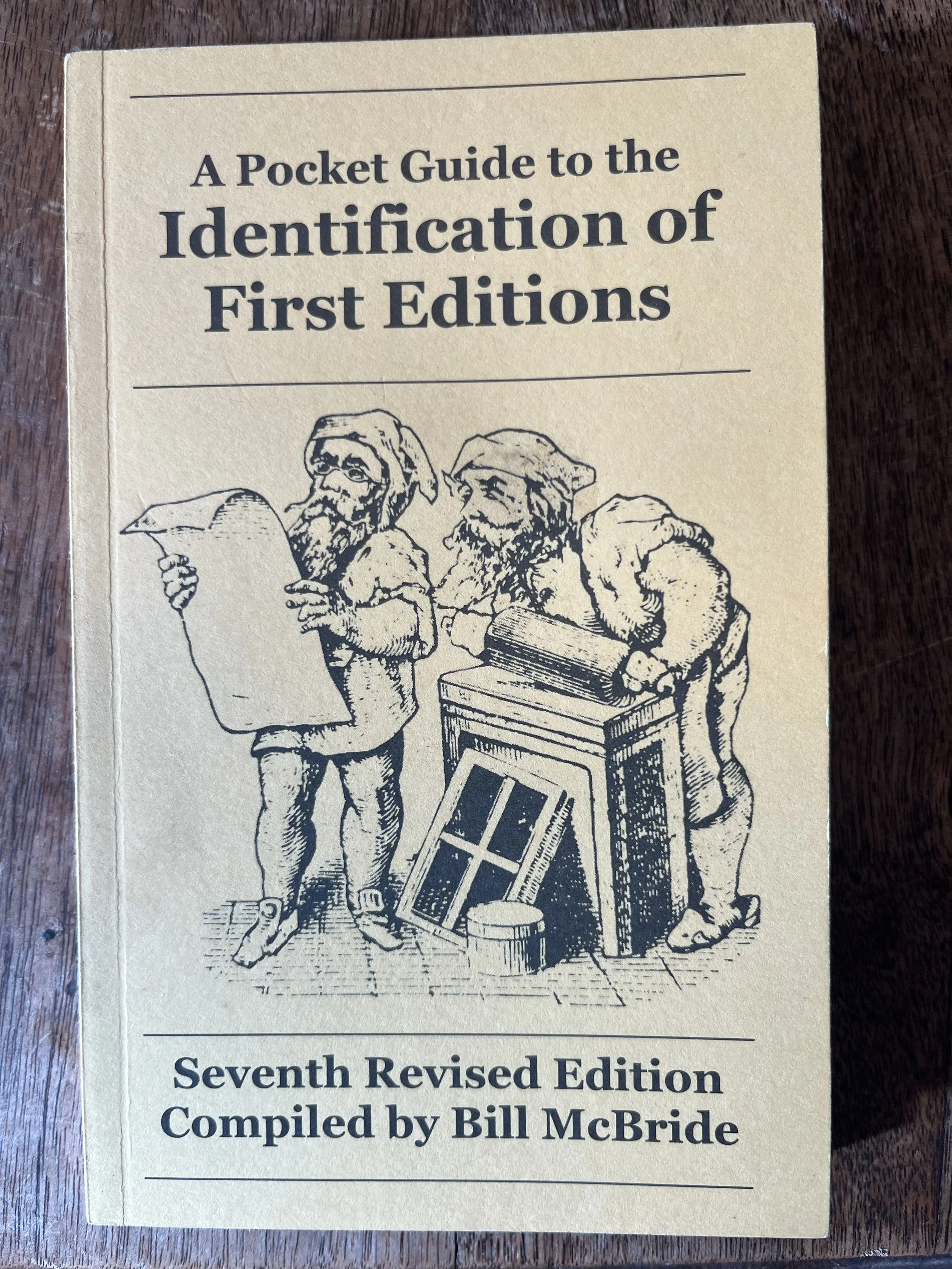

An invaluable tool.

For guidance in determining how different publishers indicate a first edition, I highly recommend the little paperback A Pocket Guide to the Identification of First Editions by Bill McBride (7th revised edition).

I also recommend you beware any book seller who calls a second or later printing a first edition. Yikes!